QDGset: A Large Scale Grasping Dataset Generated with QD

Augmenting grasping datasets

Recent studies are increasingly leveraging automatically generated grasping datasets to train more generalizable grasping policies. These approaches utilize advanced techniques such as diffusion models (Urain et al., 2023), Variational Autoencoders (Barad et al., 2023), and neural representations (Chen et al., 2024), paving the way for more robust robotic grasping systems.

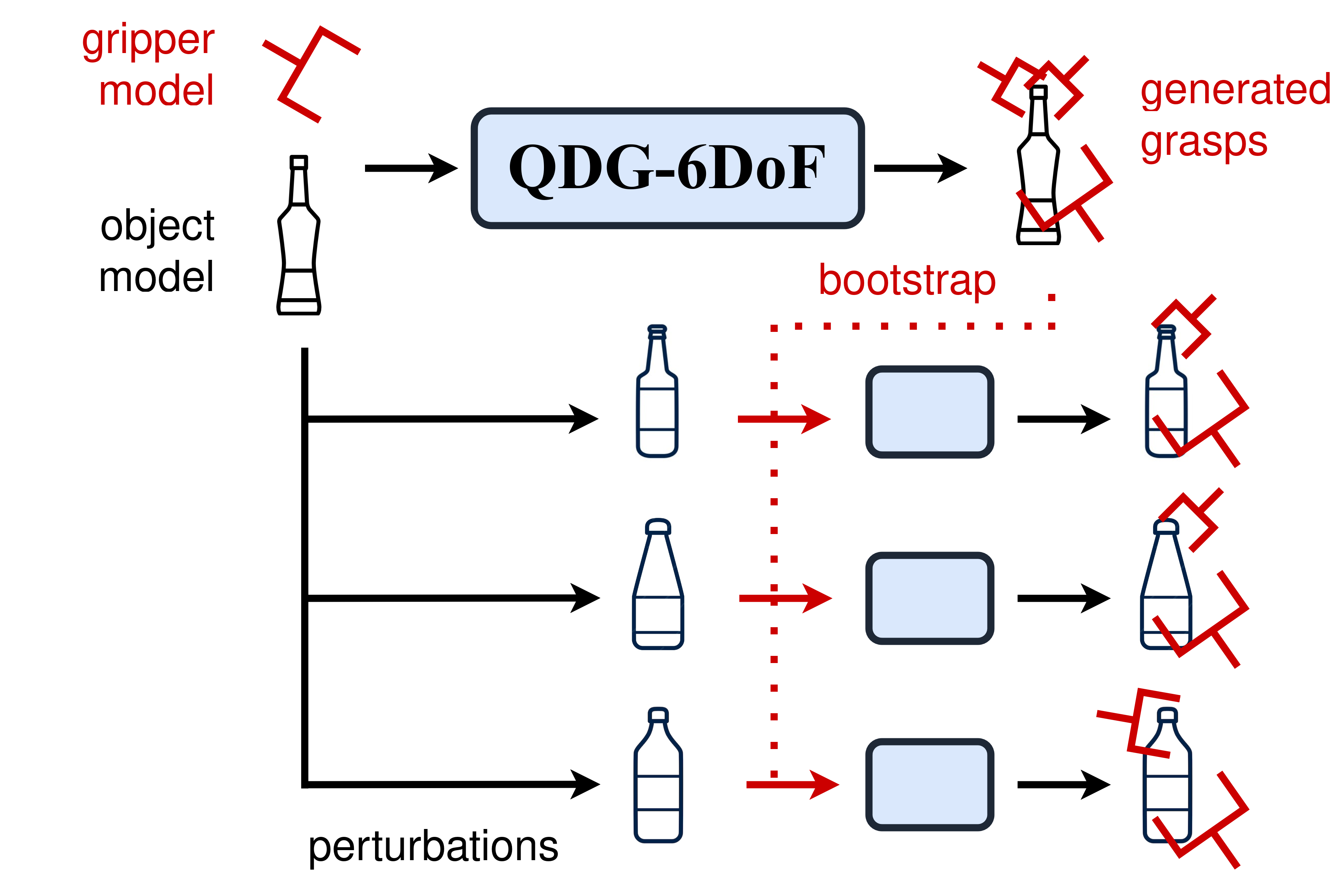

The most commonly used dataset is ACRONYM, a large set of object-centric 2-finger grasp poses (Eppner et al., 2021). ACRONYM has been generated with basic sampling schemes, which were proven significantly less sample efficient than a quality-diversity-based approach. The corresponding framework, QDG-6DoF, combines Quality-Diversity optimisation (Cully et al., 2022) with robotic priors to accelerate the discovery of diverse and robust grasps.

Some works on grasping datasets rely on data augmentation to increase the amount of high-quality data. But most of these methods concern images (Mahler et al., 2017)(Van Molle et al., 2018). In this work, we argue that object-centric grasping data can also be augmented. To do so, we proposed to create new object 3D models of objects out of known ones and to leverage previously found grasps to transfer them to the produced objects.

Proposed approach

Grasps are first generated on a given object with QDG-6DoF (Huber et al., 2024). The object's 3D model is modified by applying randomly sampled linear perturbation along the Cartesian axes. Grasp poses on the resulting objects are then produced by initializing the QDG-6DoF optimization with the success archive of the reference object.

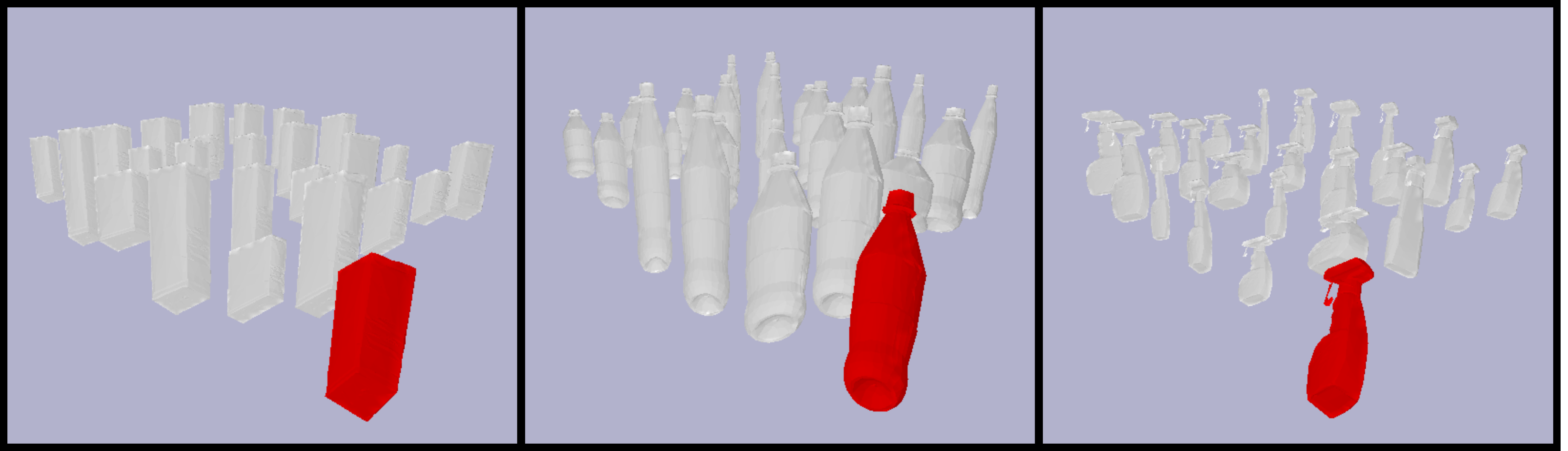

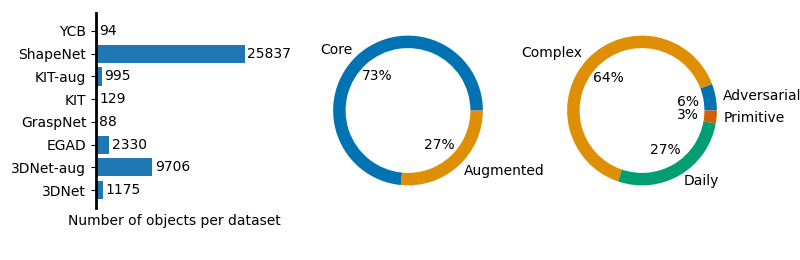

This framework relies on the assumption that a set of realistic 3D models of objects is available. We gathered 3D models coming from KIT (Kasper et al., 2012), 3DNet (Wohlkinger et al., 2012), YCB (Calli et al., 2015), GraspNet-1Billion (Fang et al., 2020), and ShapeNet (Chang et al., 2015) datasets. EGAD (Morrison et al., 2020) is also included, even if it contains unrealistic objects. These models have been generated to explore grasping capabilities on adversarial objects—this is why it is included, too.

The follow-up assumption is that applying linear perturbations on the geometrical axes of a realistic object resultsresults in a new, still realistic object. The above image shows three examples that support that view.

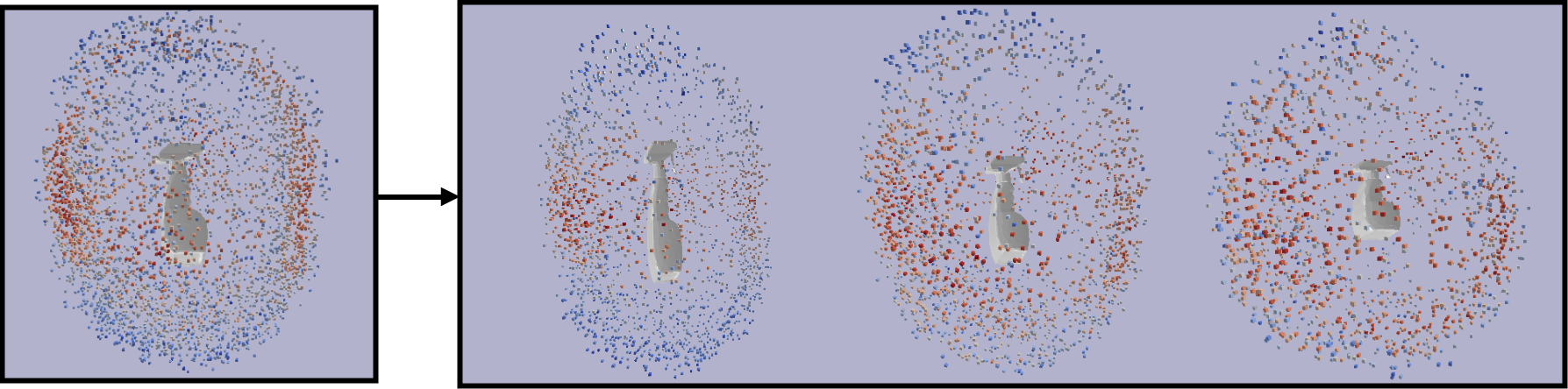

These new objects are, however, relatively close to the reference model from which they were generated. Thus, grasp poses that are successful on the reference object are likely to be successful on the new one. The success archives of a QDG-6DoF optimization should therefore be a good starting point for a new optimization on an augmented object.

Experimental results

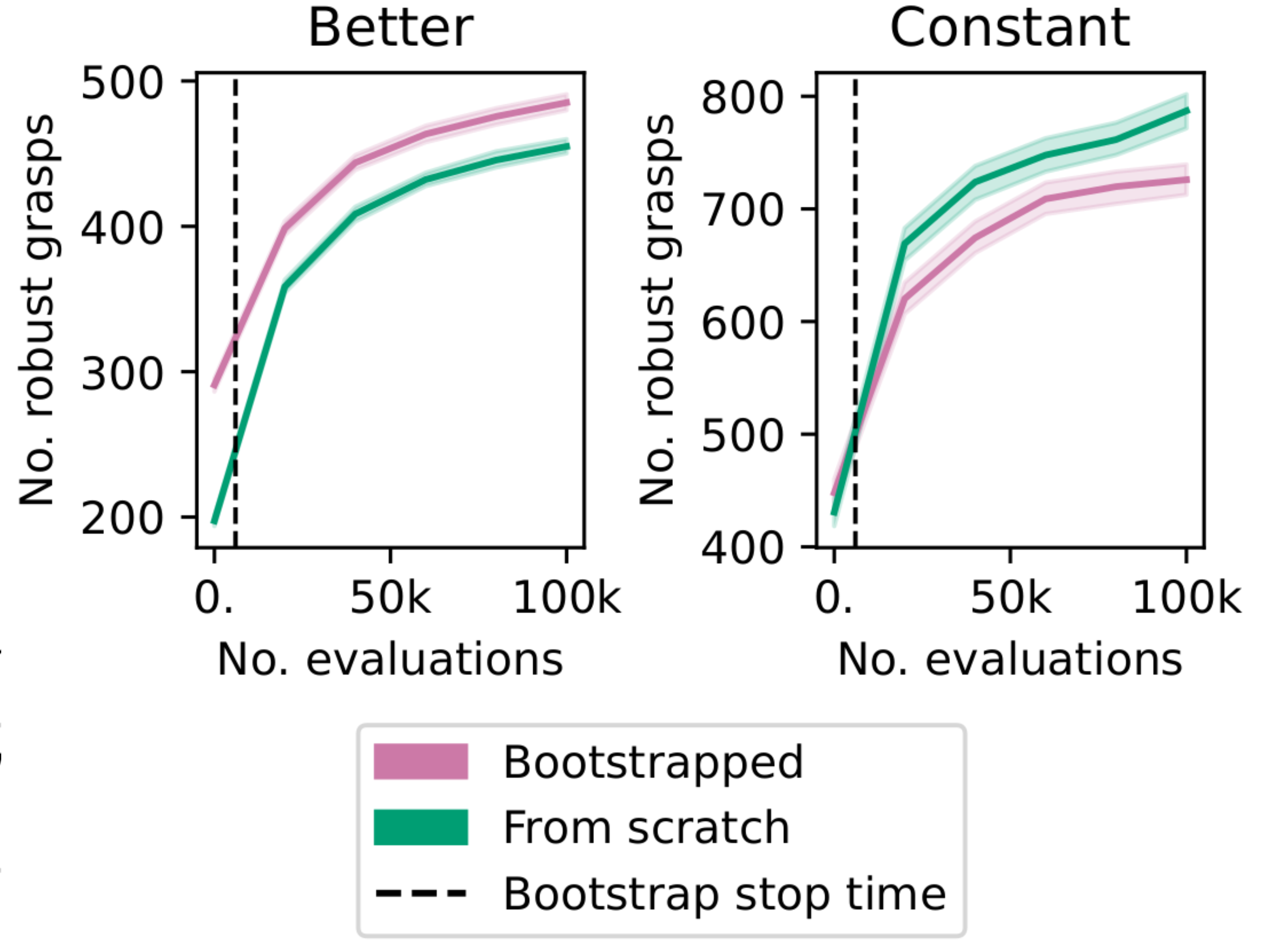

In an experimental study, 76% over the 431 runs lead to more robust grasps when stopping after the bootstrapping step. However, the bootstrap can have a detrimental effect on the long run for some objects. The above plot presents the evolution of the number of successful grasps found in runs of QDG-6DoF with and without bootstrap. These results show that the bootstrapping approach has a positive - or at least null - effect on the sample efficiency of the optimization process. However, using a previously found archive as input for initializing has a null, or at worse, negative impact on the sample efficiency. Consequently, the proposed approach is efficient in speeding up QD optimization if the process is stopped right after the bootstrapping step.

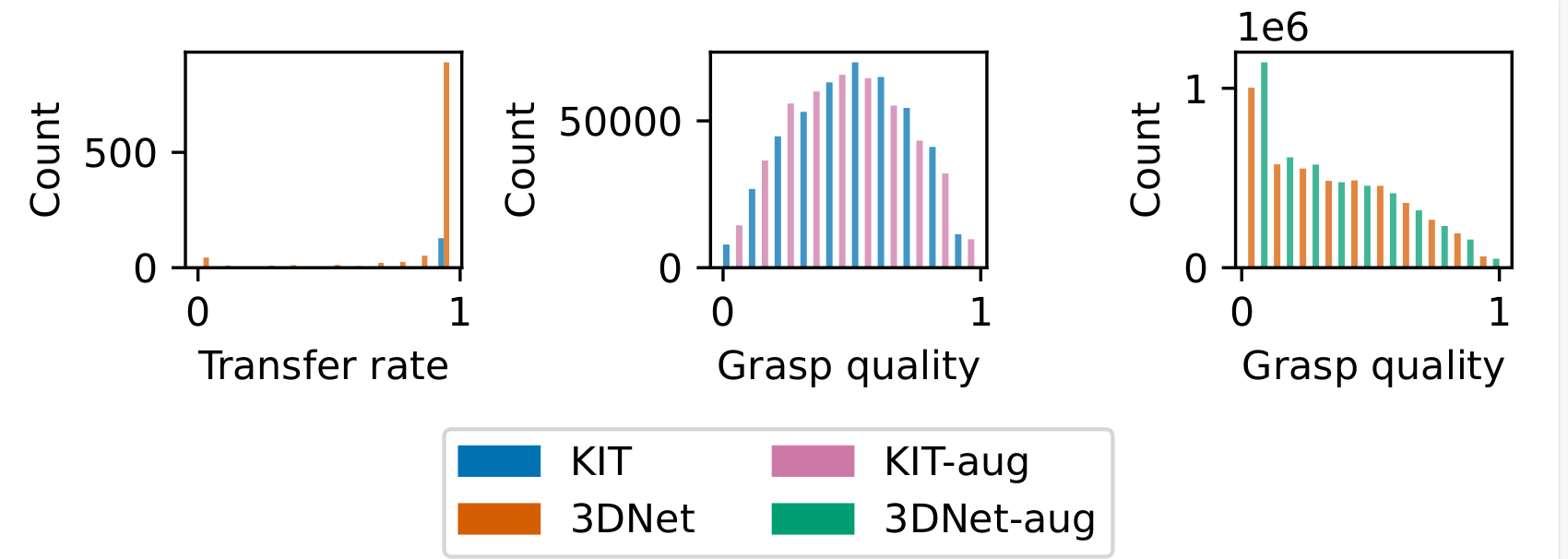

For 78% of the 1304 considered reference objects, 10 out of 10 transfers lead to at least 500 successful grasps. Moreover, the distributions of grasp qualities are similar for the reference grasp sets and the augmented ones. This shows that the proposed bootstrapping method leads to successful transfer from core objects to augmented ones while maintaining the same quality distribution.

In an experimental study, 76% over the 431 runs lead to more robust grasps when stopping after the bootstrapping step. However, the bootstrap can have a detrimental effect on the long run for some objects. The above plot presents the evolution of the number of successful grasps found in runs of QDG-6DoF with and without bootstrap. These results show that the bootstrapping approach has a positive - or at least null - effect on the sample efficiency of the optimization process. However, using a previously found archive as input for initializing has a null, or at worse, negative impact on the sample efficiency. Consequently, the proposed approach efficiently speeds up QD optimization if the process is stopped right after the bootstrapping step.

QDGset

Building on these results, we have created QDGset, a large-scale dataset of 62.000.000 object-centric grasp poses for about 40.000 objects. Each grasp is labeled with a probability to transfer in the real world, using the domain-randomization-based criterion introduced in a previous work.

QDGset contains objects from a wide range of object datasets—including primitive, daily, complex, and adversarial objects. Some of them are widely used for benchmarking in the physical world, like the YCB set (Calli et al., 2015), or can be 3d printed (Morrison et al., 2020). Only 27% of the current set comes from augmentations: the size of the dataset can thus easily be scaled by orders of magnitude.

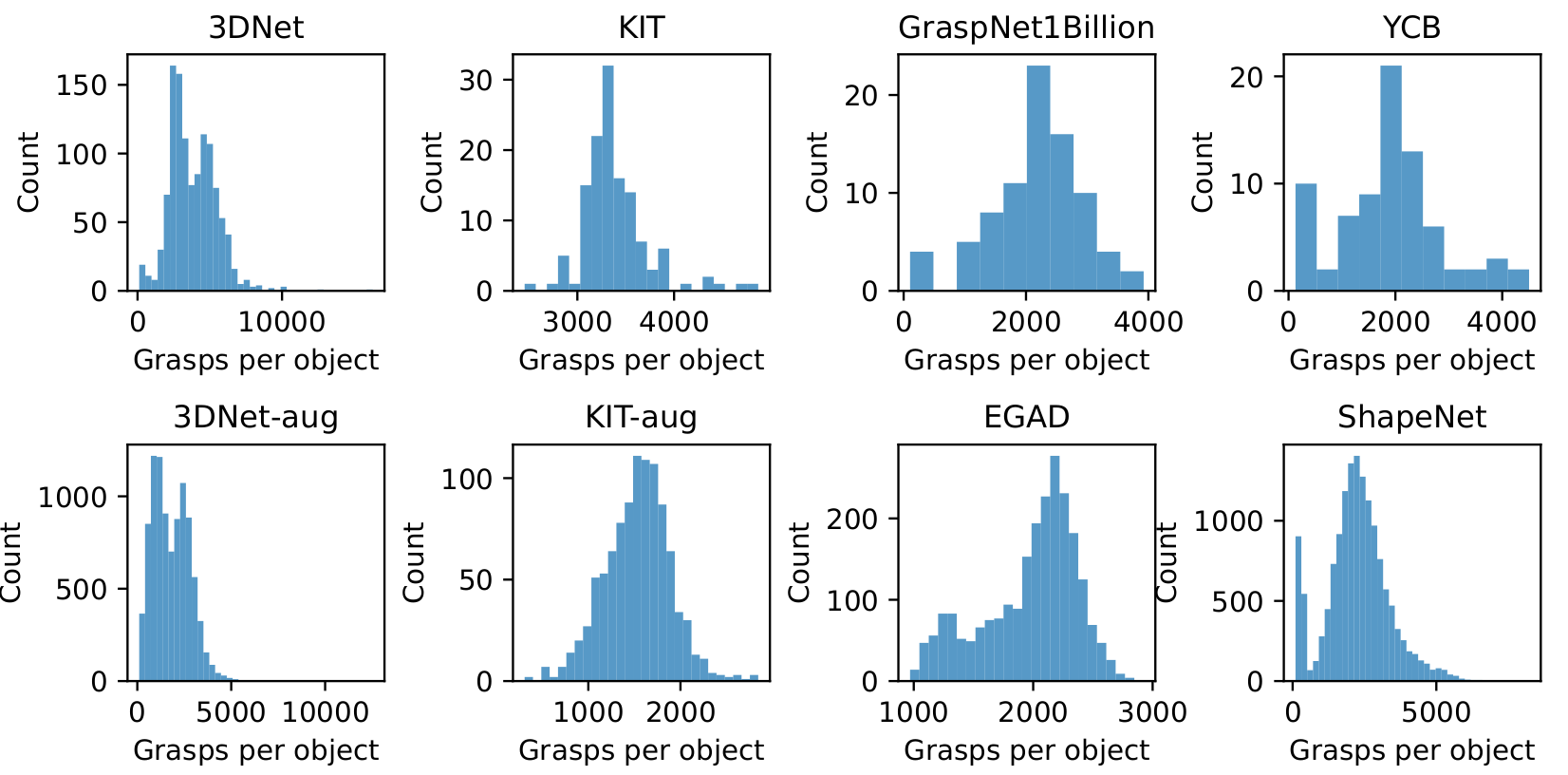

Most of the objects yield from 1000 to 5000 grasp poses. The obtained distributions of number of success found per objects shows how diverse in complexity the objects are: many more grasps were found on the KIT objects than the EGAD. This allows us to fully explore the capability of a given gripper on objects depending on their geometry. Leveraging such a large dataset for learning grasping policies, as it has been done on ACRONYM, is a promising perspective of this work.

The ease of grasp generation with QDG-6DoF allows anyone to extend QDGset with more grasp for the panda 2-finger gripper. As QDG-6DoF is versatile to the gripper type, QDGset can similarly be extended with other kinds of grippers using the same codebase. The current approach, however, is limited to exploring the interaction between the contact 3D models of a gripper and an object. It assumes that the object consists of a unique material, which is not always true in the real world.

Conclusions

This work introduces QDGset, a large-scale parallel jaw grasp dataset provided as object-centric poses. It was produced by extending QDG-6DoF to data augmentation for grasping. This approach combines the creation of new simulated objects from reference ones with the transfer of previously found grasps. This method can reduce the required number of evaluations for finding robust grasps by up to 20% while maintaining the same quality distributions. The obtained results demonstrate how QD can be used to generate new data for a particular grasping scenario. We believe that such a tool makes possible the gathering of a large collaborative dataset of simulated grasps that can be successfully used in the real world.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Sorbonne Center for Artificial Intelligence, the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (01IS21080), the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) (ANR-21-FAI1-0004) (Learn2Grasp), the European Commission's Horizon Europe Framework Programme under grant No 101070381, by the European Union's Horizon Europe Framework Programme under grant agreement No 101070596, by Grant PID2021-122685OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR. This work used HPC resources from GENCI-IDRIS (Grant 20XX-AD011014320).

References

Urain, J., Funk, N., Peters, J., Chalvatzaki, G. (2023, May). Se (3)-diffusionfields: Learning smooth cost functions for joint grasp and motion optimization through diffusion. ICRA 2023.

Barad, K. R., Orsula, A., Richard, A., Dentler, J., Olivares-Mendez, M., Martinez, C. (2023). GraspLDM: Generative 6-DoF Grasp Synthesis using Latent Diffusion Models. arXiv preprint.

Chen, H., Xu, B., Leutenegger, S. (2024). FuncGrasp: Learning Object-Centric Neural Grasp Functions from Single Annotated Example Object. arXiv preprint.

Eppner, C., Mousavian, A., Fox, D. (2021, May). Acronym: A large-scale grasp dataset based on simulation. ICRA 2021.

Cully, A., Mouret, J-B., Doncieux, S. (2022). Quality-diversity optimisation. Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion.

Mahler, J., Liang, J., Niyaz, S., Laskey, M., Doan, R., Liu, X., Aparicio-Ojea, J., Goldberg, K. (2017). Dex-net 2.0: Deep learning to plan robust grasps with synthetic point clouds and analytic grasp metrics. In 2017 Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS).

Van Molle, P., Verbelen, T., De Coninck, E., De Boom, C., Simoens, P., & Dhoedt, B. (2018). Learning to grasp from a single demonstration.

Kasper, A., Xue, Z. R, Dillmann, R. (2012). The kIT object models database: An object model database for object recognition, localization and manipulation in service robotics. The International Journal of Robotics Research (IJRR), 31(8), 927-934.

Wohlkinger, W. Aldoma, A., Rusu, R.B., Vincze, M. (2012). 3DNET: Large-scale object class recognition from cad models. In 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 5384-5391). IEEE.

Calli, B., Walsman, A., Singh, A., Srinivasa, S., Abbeel, P., Dollar, A. M. (2015). Benchmarking in manipulation research: The ycb object and model set and benchmarking protocols. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine (RAM), 22(3), 36-52.

Fang, H. S., Wang, C., Gou, M., Lu, C. (2020). Graspnet-1billion: A large-scale benchmark for general object grasping. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (pp. 11441-11450). IEEE.

Chang, A.X., Funkhouser, T., Guibas, L., Hanrahan, P., Huang, Q., Li, Z., Savarese, S., Savva, M., Song, S., Su, H., Xiao, J., Yi, L., Yu, F. (2015). ShapeNet: an information-rich 3D model repository.

Morrison, D., Corke, P. Leitner, J. (2020). Egad! an evolved grasping analysis dataset for diversity and reproducibility in robotic manipulation. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters (RA-L), 8(3), 4368-4375.