Leverage QD for an easily transferable vision-based grasping module

The virtues of sequential approaches for grasping: energy cost, and interpretability

Data-greedy approaches are becoming the main paradigm in robotics nowadays. Grasping is more and more addressed with generative AI methods (Urain et al., 2023)(Barad et al., 2023)(Chen et al., 2024), while the training of end-to-end controllers for mobile manipulators involves extremely large Transformers-based architecture and manually collected datasets (Brohan et al., 2023.a)(Brohan et al., 2023.b). Despite their promising generalization capabilities, the cost of those methods raises concerns about how to make such energy-demanding approaches sustainable (Thompson et al., 2020) and interpretable.

However, the usage of data-greedy methods is recent in the history of Robotics (Newbury et al., 2023). For a long time, grasping was addressed with analytic-based approaches and motion planning (Sahbani et al., 2012). The issue was the limited adaptation capabilities that the data-greedy approach can circumvent. Many skills should be addressable with significantly less energy cost than the large AI models, with enough generalization to provide robots the capability to solve a wide range of tasks in open environments while keeping a certain level of interpretability and control on the grasping robot decision process.

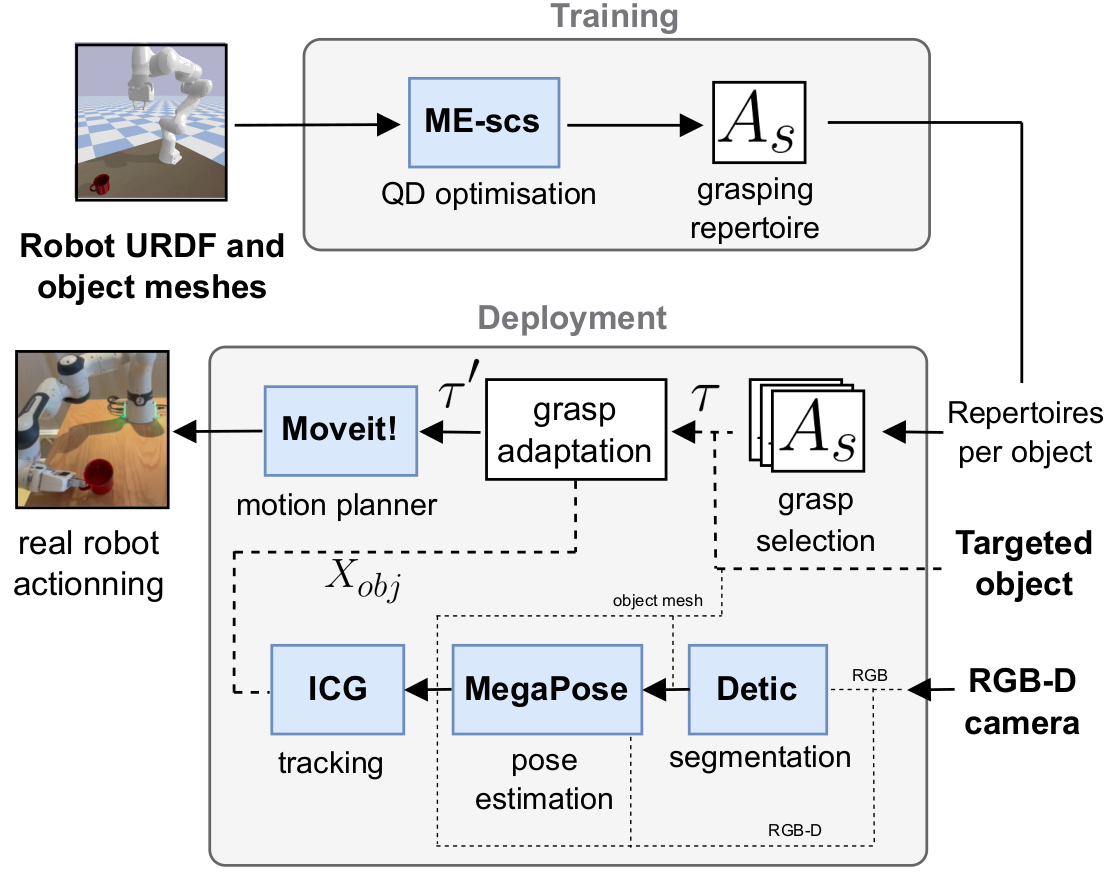

This paper introduces modular vision-based grasping framework that can be leveraged to make robots learn to grasp known objects with a limited computational cost and better control than the data-greedy approaches. Based on recent works in Quality-Diversity (QD) methods, the proposed framework builds repertoires of diverse grasping trajectories for a given robotic manipulator and a set of objects. At deployment time, a vision pipeline of open-source modules predicts the targeted object state (6DoF pose, including position and orientation). A trajectory is then selected and adapted relatively to the predicted object pose.

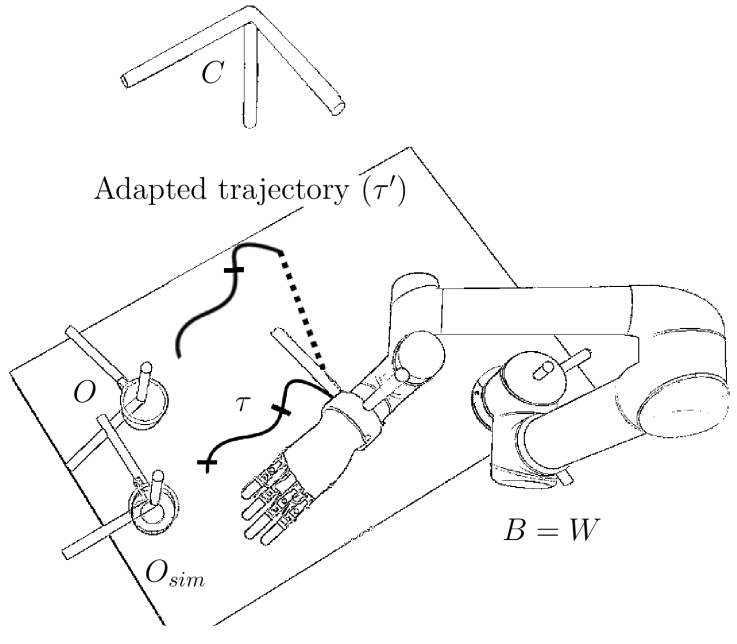

Grasp Adaptation Pipeline

Grasp Generation

The reach-and-grasp trajectories are generated with QD algorithms, similarly to (Huber et al, 2023). The automatic generation of grasps with QD is described in this related blog post.

6DoF Pose Prediction

A given object name is set as input to an Open Vocabulary segmenter (Zhou et al., 2022) that provides a first guess on the object localization in the RGB-D image through the segmented region.

The first 6DoF pose is then computed with MegaPose (Labbé et al. 2022) using the RGB-D image and the known object meshes.

Given the initial 6DoF pose, the object is then tracked with ICG (Stoiber et al., 2022).

The reach-and-grasp trajectory can finally be adapted using the tracked estimated pose.

Trajectory Adaptation

To compute the adaptation, a given grasping trajectory is first expressed as a sequence of positions and orientations in the world frame that describe the approach and the application of forces on the object. Those poses are then expressed relatively to the object frame, allowing the gripper to reach and grasp the object for any object's pose.

Such a straightforward approach modifies the initial position of the trajectory, which does not correspond to the initial end effector pose anymore. The trajectory is completed by reaching the first adapted position using a path planer.

The adapted grasping trajectory is not necessarily fully exploitable. Some poses might be out of the robot's operational space but might also lead to autocollisions or collisions with the environment (e.g., the table). The adapted trajectories are thus truncated to maximize the length of consecutive poses from the trajectory, which are reachable while assuring to preserve the prehension pose. In the worst case, the 6DoF prehension poses might be invalid. It is worth noting that the large diversity of QD generated grasps guarantees to provide several grasping solutions for a considered object pose.

Scene and trajectory update

The above animation shows the adaptation of a QD-generated grasping trajectory to the predicted object 6DoF pose. In green is the object pose at which the grasp has been generated in simulation. The colored curve above the mug is the sequence of states the end effector must follow to grasp the object. The green, blue, and red arrows represent the corresponding orientations. The pipeline provides an adapted trajectory to follow for any predicted object position, allowing the exploit of automatically generated datasets for any targeted position in the operational space.

Results

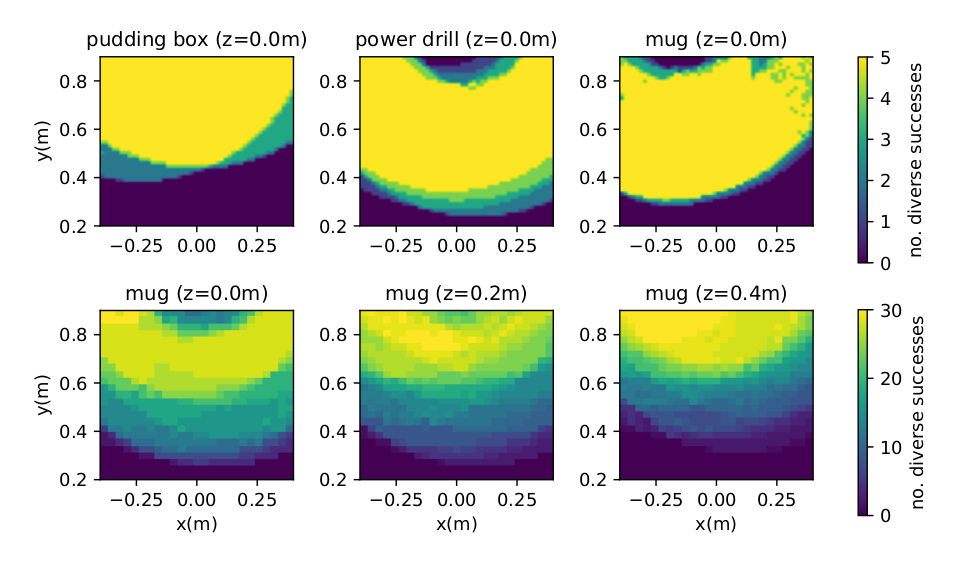

Generalisation to the whole operational space

As previously mentioned, the simple adaptation method proposed in this article does not necessarily lead to valid grasp trajectories. To evaluate to what extent the automatically generated grasps can be exploited with the adapation without having to sample other grasps from a QD generated dataset, a specific experiment has been conducted in simulation. It consists of estimating the number of valid grasps after adaptation for a wide range of object positions and orientations. The above-presented results show that the adaptation almost always leads to valid grasps when translating the object (top row) – except when the positions are too far from the robot (out of range) or too close (leading to autocollision). When applying both translation and rotation (bottom row), the ratio of successful adaptation is lower. The rotations often require truncation of the approaching phase, making the grasp's success more dependent on the path planner. Plus, the 6-DoF prehension can be projected into obstacles, making them unreachable. Nevertheless, a significant part of the trajectories can straightforwardly be applied to new object positions without compromising the success of the grasp.

Real world reach-and-grasp trajectory adaptation

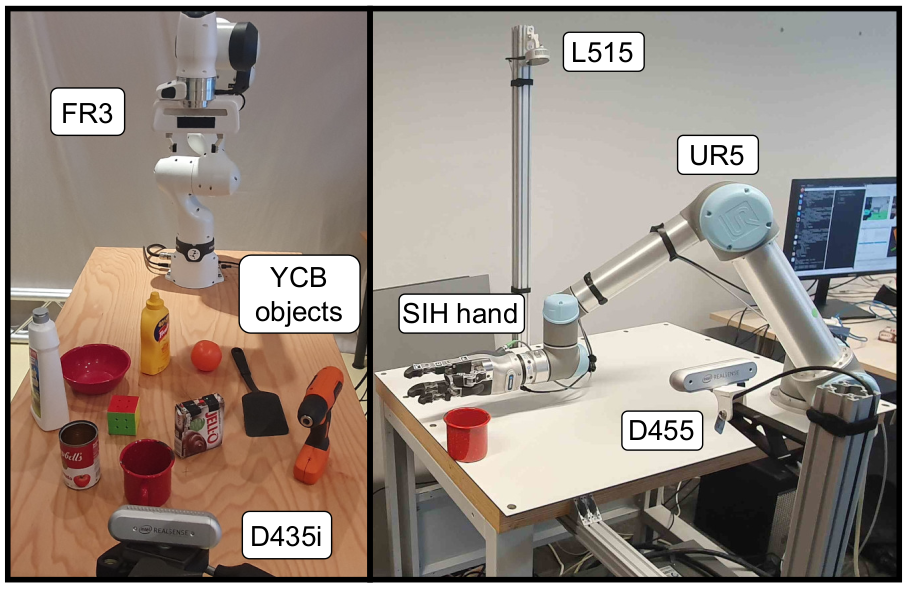

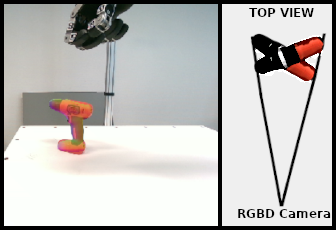

The approach has been validated on two real robots: a Franka Research 3 arm with a 2-fingers gripper and a UR-5 arm with an SIH Schunk Hand. Some grasping trajectories have been generated with the ME-scs QD algorithm (Huber et al., 2023). A subset of the YCB objects (Calli et al., 2015) has been used for the experiments.

It is worth noting that 3 different RGB-D camera has been used: a D435i camera positioned with a 45° angle point-of-view on the scene for the FR3 arm; a L515 with a 90° angle, and a D455 with a 0° angle point-of-view on the scene for the UR5 arm. The proposed approach exploits a single RGB-D camera at a time. What is notable is that the perception part of the proposed approach operates similarly with any of those 3 kinds of RGD-D camera, being similarly robust to the 3 point-of-views. We believe this property to be a key strength of the proposed approach, considering the challenges of 6-DoF object pose estimators on real scenes (Tyree et al., 2022).

The results obtained on the real robot validate the simple adaptation strategy for two robotic manipulators of different natures, preserving the benefits of QD methods for easy generalization to different plateforms. It also preserves the diversity of grasps regarding the quality (more or less robust grasps) and the affordances (diverse application of forces on the object for accomplishing certain tasks afterward).

Limits

This work has some limitations. First, the vision noise can lead to wrong 6DoF pose estimation and limit the transferability of some grasps. Moreover, some object surfaces are slippery, especially with only two fingers, when applying too much force on the object surface. The proposed approach is also not close-loop adaptation: as soon as the grasping trajectory deployment is started, the modification of the object state will not be taken into account on the flight.

Conclusions

This paper proposes a framework to build a plug-and-play vision-based grasping module. It can easily be adapted to different robotic platforms and allows the robot to robustly grasp objects in a diverse manner. We believe this modular framework to be an affordable alternative to the computationally greedy foundation-model-based approaches and a promising path to make different kinds of mobile robots interact with known objects in a controllable manner in the near future.

Acknowledgement

Authors deeply thank Pr. Sven Behnke and the members of the AIS lab of Bonn for their warm welcome and support.

This work was supported by the Sorbonne Center for Artificial Intelligence, the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (01IS21080), the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) (ANR-21-FAI1-0004) (Learn2Grasp), the European Commission’s Horizon Europe Framework Programme under grant No 101070381 and from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Framework Programme under grant agreement No 101070596. This work used HPC resources from GENCI-IDRIS (Grant 20XX- AD011014320).

References

Urain, J., Funk, N., Peters, J., \& Chalvatzaki, G. (2023, May). Se (3)-diffusionfields: Learning smooth cost functions for joint grasp and motion optimization through diffusion. ICRA 2023.

Barad, K. R., Orsula, A., Richard, A., Dentler, J., Olivares-Mendez, M., \& Martinez, C. (2023). GraspLDM: Generative 6-DoF Grasp Synthesis using Latent Diffusion Models. arXiv preprint.

Chen, H., Xu, B., \& Leutenegger, S. (2024). FuncGrasp: Learning Object-Centric Neural Grasp Functions from Single Annotated Example Object. arXiv preprint.

Brohan, A., Brown, N., Carbajal, J., Chebotar, Y., Dabis, J., Finn, C., …& Zitkovich, B. (2022). Rt-1: Robotics transformer for real-world control at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.06817.

Brohan, A., Brown, N., Carbajal, J., Chebotar, Y., Chen, X., Choromanski, K., …& Zitkovich, B. (2023). Rt-2: Vision-language-action models transfer web knowledge to robotic control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.15

Thompson, N. C., Greenewald, K., Lee, K.,& Manso, G. F. (2020). The computational limits of deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.05558.

Newbury, R., Gu, M., Chumbley, L., Mousavian, A., Eppner, C., Leitner, J., …& Cosgun, A. (2023). Deep learning approaches to grasp synthesis: A review. IEEE Transactions on Robotics.

Sahbani, A., El-Khoury, S.,& Bidaud, P. (2012). An overview of 3D object grasp synthesis algorithms. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 60(3), 326-336

Huber, J., Hélénon, F., Coninx, M., Ben Amar, F., Doncieux, S. (2023). Quality Diversity under Sparse Reward and Sparse Interaction: Application to Grasping in Robotics. arXiv:2308.05483

X. Zhou, R. Girdhar, A. Joulin, P. Krähenbühl, and I. Misra, “Detecting Twenty-Thousand Classes Using Image-Level Supervision,” in Computer Vision – ECCV 2022, S. Avidan, G. Brostow, M. Cissé, G. M. Farinella, and T. Hassner, Eds. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022, vol. 13669, pp. 350–368.

B. Calli, A. Singh, A. Walsman, S. Srinivasa, P. Abbeel, and A. M. Dollar, “The YCB object and Model set: Towards common benchmarks for manipulation research,” in 2015 International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), July 2015, pp. 510–517.

Tyree, S., Tremblay, J., To, T., Cheng, J., Mosier, T., Smith, J., & Birchfield, S. (2022, October). 6-DoF pose estimation of household objects for robotic manipulation: An accessible dataset and benchmark. In 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (pp. 13081-13088). IEEE.

Y. Labbé, L. Manuelli, A. Mousavian, S. Tyree, S. Birchfield, J. Tremblay, J. Carpentier, M. Aubry, D. Fox, and J. Sivic, “MegaPose: 6D Pose Estimation of Novel Objects via Render & Compare,” in 6th Annual Conference on Robot Learning, Aug. 2022.

M. Stoiber, M. Sundermeyer, and R. Triebel, “Iterative Corresponding Geometry: Fusing Region and Depth for Highly Efficient 3D Tracking of Textureless Objects,” in 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). New Orleans, LA, USA: IEEE, June 2022, pp. 6845–6855.