Labelling Grasps for Sim2Real Transfer

Bridging the Reality Gap for Grasping

Getting large datasets of simulated grasps is insufficient to make real robots seize objects. The differences between the simulated and real scenes can make high-performing solutions in simulation inefficient in reality. This issue is known as the reality gap and has been widely discussed in the literature (Salvato et al, 2021).

The reality gap raises many challenges for exploiting automatically generated grasps: Is there a way to distinguish the solutions most likely to transfer into the real world? Can we drive the Quality-Diversity (QD) optimization process toward the generation of more robust grasps to sim2real transfer? What are the main reasons for simulation exploit, that is, the main sources of discrepancy between simulation and reality the algorithm can target to produce non-transferable grasps?

Exploiting automatically generated datasets for learning to grasp requires high-quality labels. To make the learned policies efficient in the real world, the labels should express the transferability of the grasp – that is, its probability of success when deployed into the real world.

This work aims to estimate the transferability associated with automatically generated grasps to provide such labels.

How to estimate Transferability

Many works on grasping rely on analytics criteria to estimate transferability (Nguyen, 1988). This work relies on another approach, leveraging the simulation of interactions between robotic grippers and objects to produce transferable grasps. In both cases, estimating the sim2real transferability is a very challenging task. The literature on sim2real robotics eventually do measures on the real robots and compare them with the simulation to quantify the gap (Koos et al, 2012).

In this work, we have automatically generated and deployed more than 7000 reach-and-grasps trajectories for 3 different robot-grippers setups and 33 objects to grasp. These trajectories have been produced with 3 different QD methods to show the generalization of the obtained results.

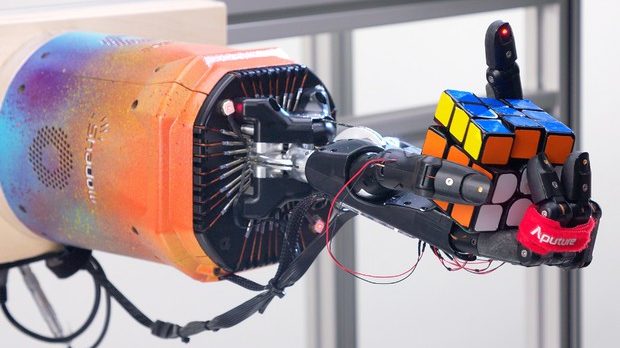

To estimate the sim2real transferability, we introduce 4 quality criteria based on Domain-Randomization. Domain Randomization consists of injecting noise into a simulated scene to make the produced solutions more robust to sim2real transfer (Muratore et al, 2022). This approach has led to great results in robot skill learning (Akkaya et al, 2019).

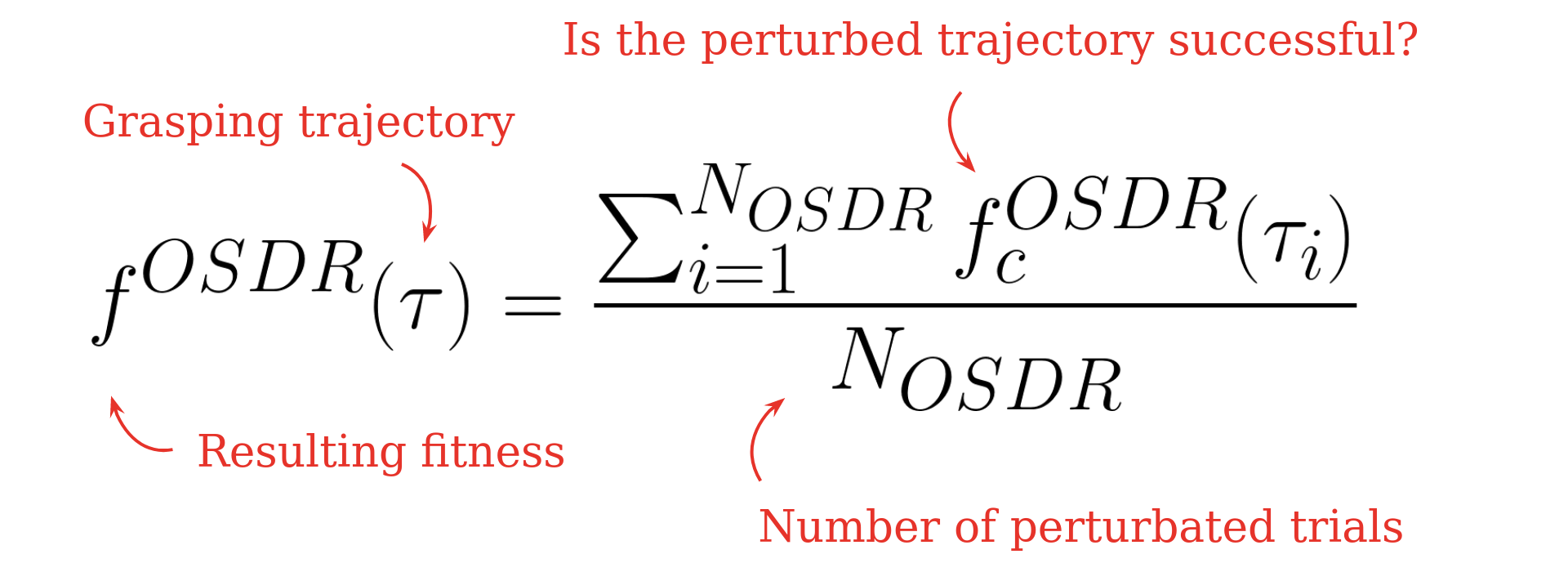

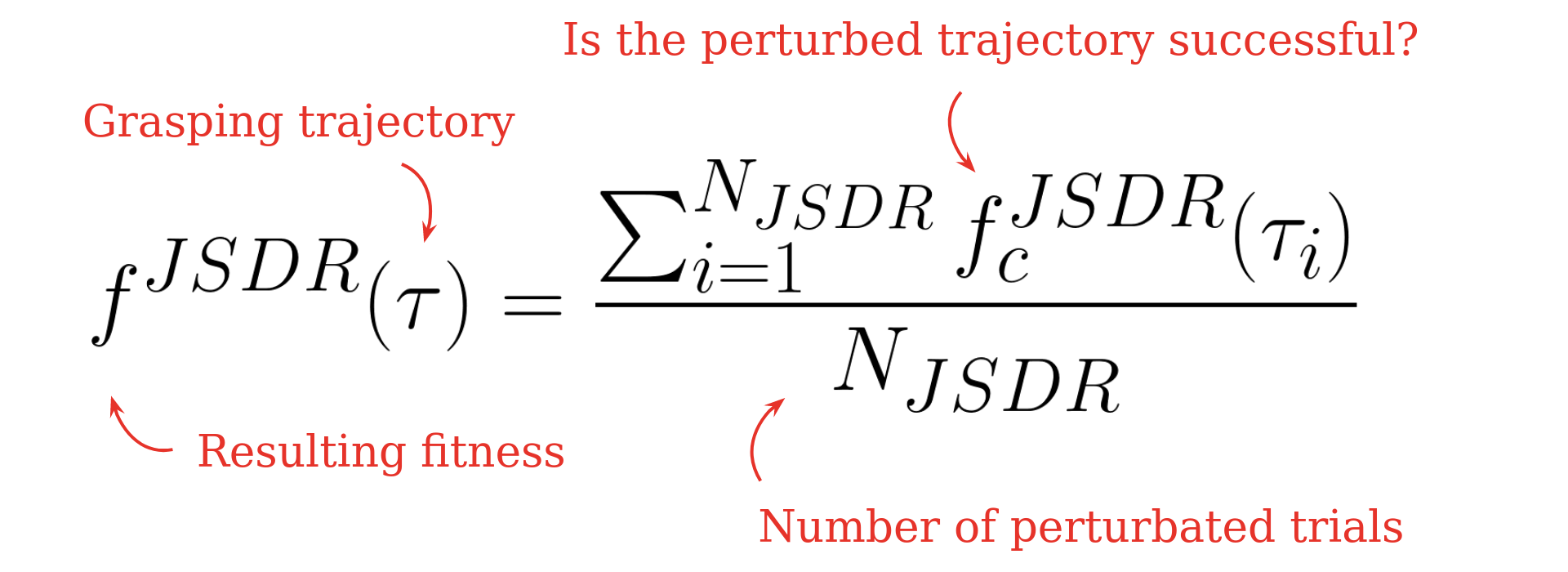

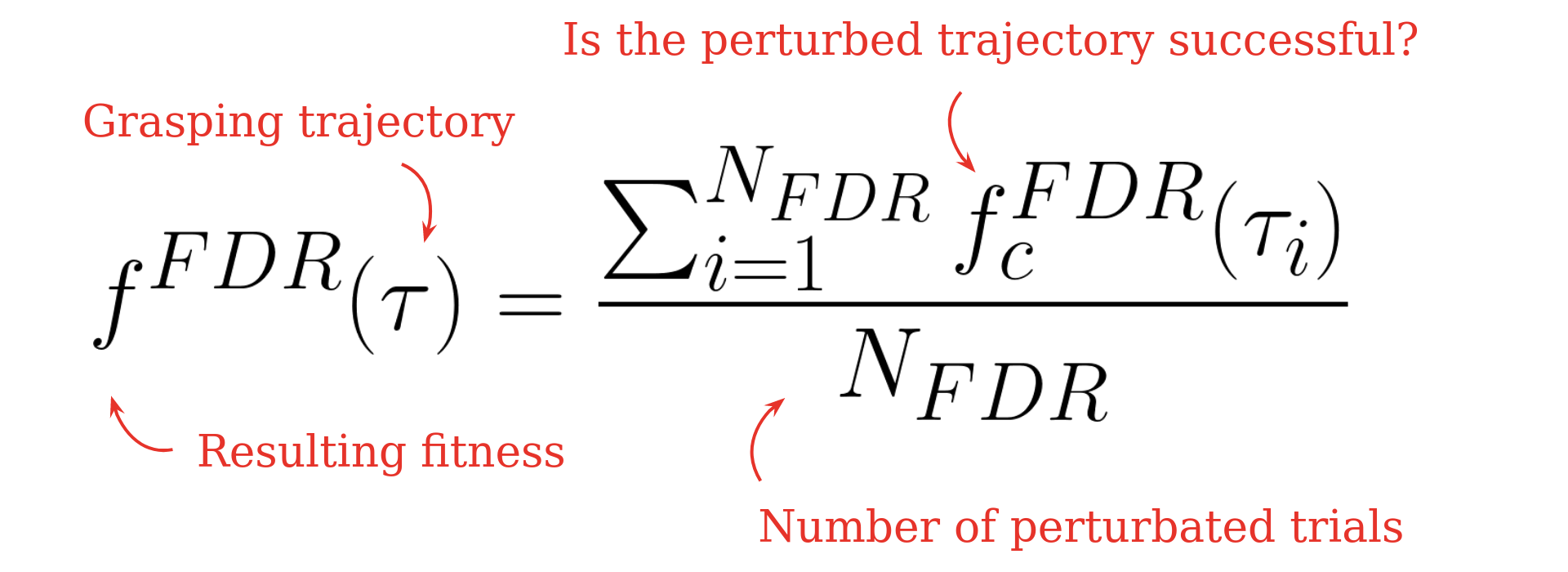

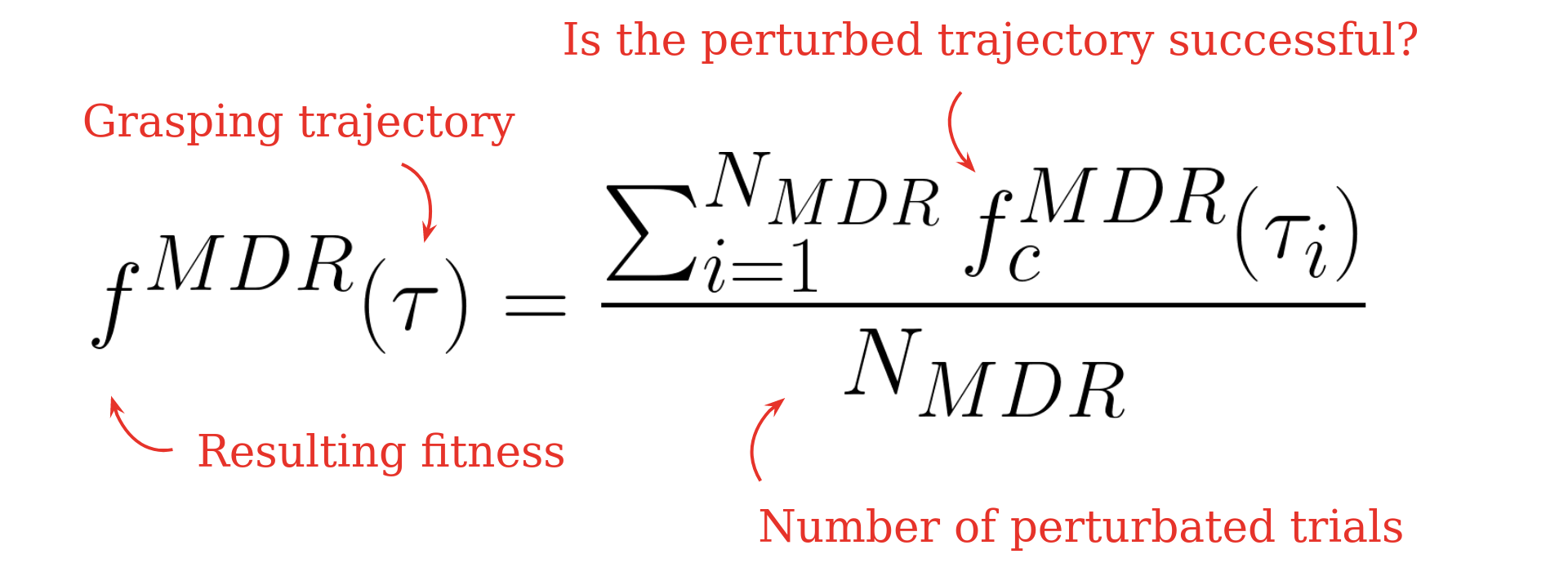

The Domain-Randomization-based quality criteria aim to mimic some sources of noise in real grasping setups. These quality criteria are exploited as fitness functions that estimate the quality of an individual – here, a given reach-and-grasp trajectory. Each fitness corresponds to the ratio of successful grasp when deploying a unique trajectory several times under different noise conditions:

• Perception noise: Designing reliable vision systems for robotic grasping is very challenging [32]. Any vision-based grasping system should thus be robust to perturbation of the object 6-DoF pose estimation. This first criterion is computed by redeploying a successful grasp several times in simulation with a perturbated object initial state (Object State Domain Randomization, OSDR).

• Control noise: Real robots are submitted to stochasticity due to variations of the environment’s conditions or wear-and-tear [33], causing reproducibility issues [34]. This quality criterion is computed as the robustness to perturbations on the joint states (Joint States Domain Randomization, JSDR).

• Dynamics noise: Simulators for learning in robotics do not perfectly reproduce the real-world dynamics [35]. The third quality criterion expresses the robustness to perturbation of simulator dynamics (Frictions Domain Randomization, FDR).

• Mixture noise: While it is possible to investigate the abovementioned uncertainties separately in simulation, these issues must be addressed simultaneously when working with real robots. The combination of each of these DR methods is the fourth and the last studied quality criterion (Mixture Domain Randomization, MDR).

Let us consider the noise in the object's initial state, that is, the perception noise. An individual's fitness is 1 if the grasp is successful for various initial positions and orientations of the targeted object. Such a grasp should thus be robust to perception noise in the real world, as a slight perturbation in the object state does not compromise the success of the grasp. On the contrary, a fitness of 0 means that a successful grasp under the deterministic conditions in which the QD algorithm operates fails for any of the attempted perturbations on the object state. This makes this grasp highly dependent on the object's initial pose, such that the perception noise is likely to make the grasp fail in the real world.

Multi-plateform grasping experiment

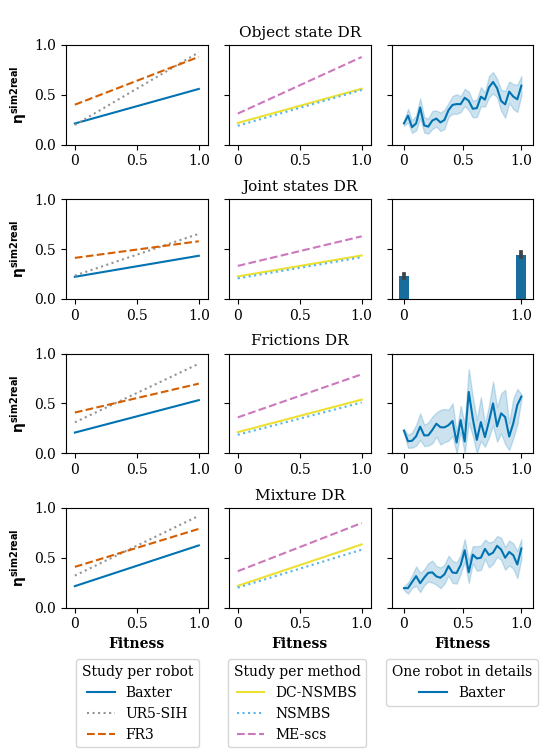

The above figure shows the relation between the sim2real transferability ratio and the domain-randomization-based fitnesses of the corresponding grasps. The results aggregated per robot (left column) and per method (center column) verify the hypothesis: the proposed fitnesses are positively correlated with the sim2real transferability. The same tendency is observed for any of the 3 robots and the 3 considered methods. It stresses that this result generalizes well regardless of the operating platform and the QD method used for generating the data.

The last column shows the obtained tendencies in detail for the platform on which the largest amount of grasps has been deployed. This shows how fine are the evaluation capabilities of each quality criterion. For example, the fitness based on domain randomization applied to the object's initial state results in fitnesses that are well split in the [0;1] interval. This criterion can thus be used to sort a list of grasps with respect to the predicted probability to transfer, distinguishing several degrees of robustness. On the contrary, the fitnesses based on domain randomization applied on the friction coefficients result in a rough classification: most of the computed fitnesses are either 0 or 1, expressed by the large variance of transferability ratios for intermediate values. Domain Randomization applied to joint states is even more binary, as almost all the computed fitnesses are 0 or 1. The proportion of other values made them considered outliers and discarded.

Increasing Sim2Real Transferability

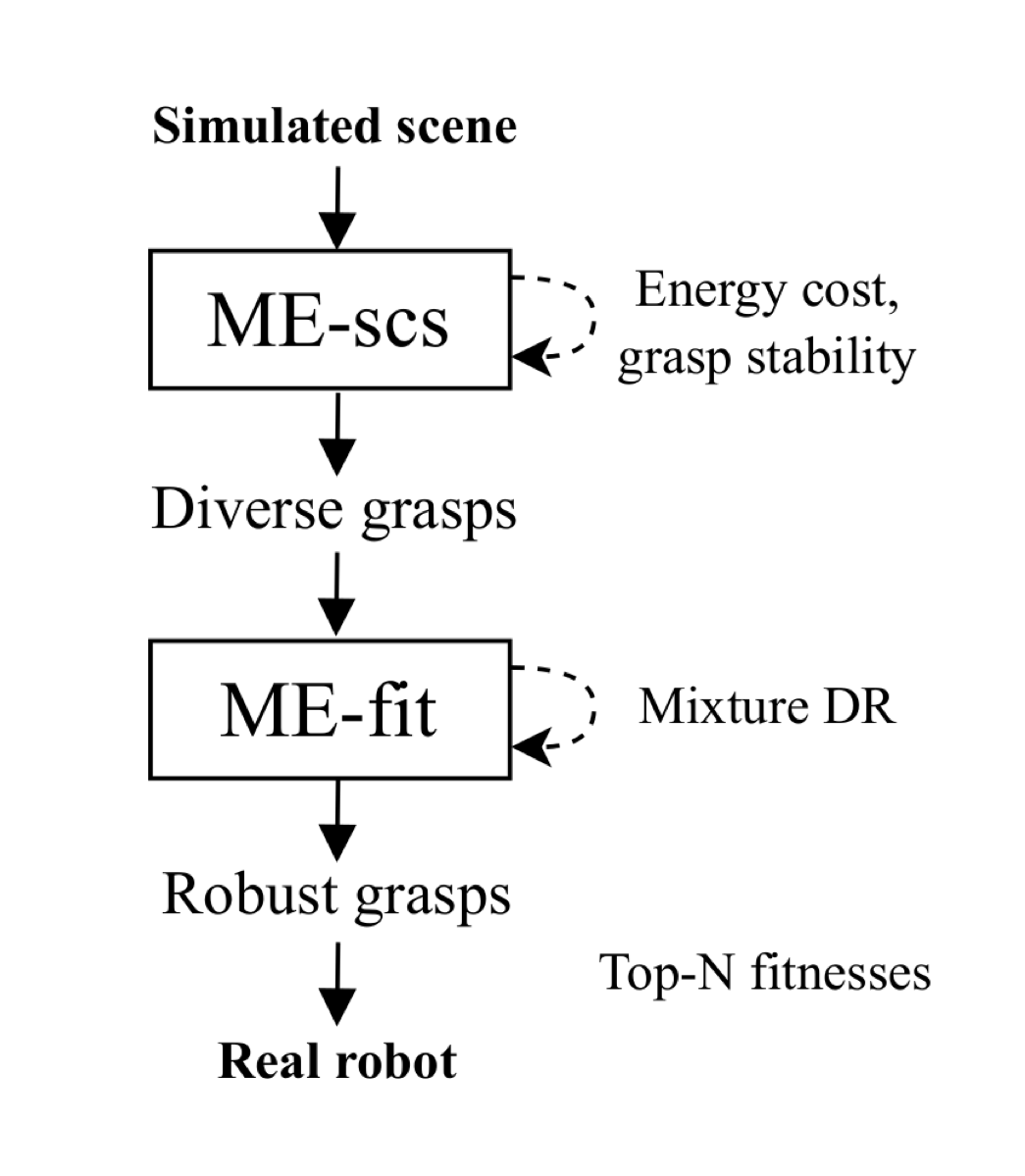

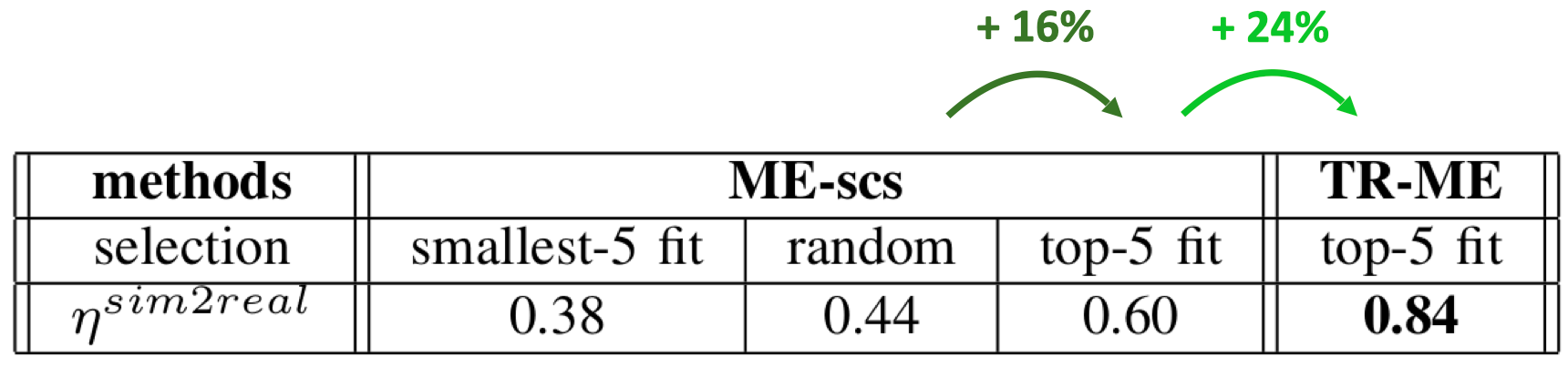

The correlation between the proposed quality criteria and the sim2real transferability suggests that those criteria can be leveraged to increase the sim2real transferability. Selecting the grasps with the higher fitness values already increases the success ratio by 16%. Further, directly optimizing these quality criteria should result in a higher transferability ratio. To test this hypothesis, the grasps that have been generated for the multi-platform grasping experiment were used to bootstrap a quality-greedy algorithm (ME-fit, see (Huber et al, 2023) optimizing the Mixture Domain Randomization fitness criteria. The resulting grasps have then been deployed, reaching about 84% of transferability ratios on the Franka Research 3 robot.

Causes of Reality Gap

Another use of the quality criteria is identifying the issues that cause the reality gap. As the generated grasps with low-quality criterion values are less likely to transfer into the real world, visualizing them among the thousands of successful solutions allows to infer what the simulation weakness exploited by the algorithm to produce fragile grasps.

Next are presented the most salient issues:

1) Coarse modelization of frictions.

The simulated scene considers a unique set of friction coefficients for each object, while their surface usually comprises different textures. In the above-shown case, the successful grasp in simulation slips from the finger in reality.

2) Coarse modelization of contacts.

Inaccurate modelization of collisions can lead to successful grasps that are infeasible in reality (e.g. insert the gripper in some part of the object to lift it).

3) Coarse modelization of inertia.

A coarse approximation of the object distribution of mass can lead to unrealistic interaction dynamics, like applying forces on an object side to lift it and grab it in the air.

4) Coarse approximations of the 3D models.

Coarse approximations of the 3D models. The difference between a simulated model and the real object is often a cause of transfer failure. Fig. 5.d shows that the coarse model of YCB padlock results into grasps on inexisting parts of the object.

5) Fragile grasps.

Some grasps in deterministic simulation can simply be not robust enough to successfully transfer into the real world.

Conclusion

This work investigates how Domain Randomization can be leveraged to compute quality criteria that are correlated with the probability of a grasp to transfer into the real world successfully. Such criteria can be exploited to generate more robust grasps and identify the simulation weaknesses that cause the discovery of simulated grasps that fail when deployed on a real robot.

These quality criteria can thus be seen as labels for the sim2real transferability of automatically generated grasps, opening perspectives on their exploitation for direct usage on known objects or learning for unknown objects.

Acknowledgement

Authors deeply thank Pr. Sven Behnke andthe members of the AIS lab of Bonn for their warm welcome and support.

This work was supported by the Sorbonne Center for Artificial Intelligence, the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (01IS21080), the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) (ANR-21-FAI1-0004) (Learn2Grasp), the European Commission’s Horizon Europe Framework Programme under grant No 101070381 and from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Framework Programme under grant agreement No 101070596. This work used HPC resources from GENCI-IDRIS (Grant 20XX- AD011014320).

References

Salvato, E., Fenu, G., Medvet, E., Pellegrino, F. A. (2021). Crossing the reality gap: A survey on sim-to-real transferability of robot controllers in reinforcement learning. IEEE Access, 9, 153171-153187.

Nguyen, V. D. (1988). Constructing force-closure grasps. The International Journal of Robotics Research, 7(3), 3-16.

Koos, S., Mouret, J. B., Doncieux, S. (2012). The transferability approach: Crossing the reality gap in evolutionary robotics. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 17(1), 122-145.

Muratore, F., Ramos, F., Turk, G., Yu, W., Gienger, M., Peters, J. (2022). Robot learning from randomized simulations: A review. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 31.

Akkaya, I., Andrychowicz, M., Chociej, M., Litwin, M., McGrew, B., Petron, A., … Zhang, L. (2019). Solving rubik’s cube with a robot hand. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.07113.

Huber, J., Hélénon, F., Coninx, M., Ben Amar, F., Doncieux, S. (2023). Quality Diversity under Sparse Reward and Sparse Interaction: Application to Grasping in Robotics. arXiv:2308.05483